ACS is one of the sinister diagnoses made at medical ER. The fear comes built in with the diagnosis often amplified by young felllows on call (& often times by senior consultants as well) It may appear real, from a clinical angle, but, please trust, when we deal with the whole gamut of ACS scenerios (other than STEMI), there is indeed a benign face, in many of them.

One big chunk of ACS-UA is secondary UA, where there is increased demand as in stable angina with tachycardia* . In these patients there is no plaque triggered ACS. For example, in a febrile patient who has associated HT, anemia, etc., we can witness menacingly deep resting ST depression with absolutely no thrombotic process going on in the coronary. (*Mind you, all stress-induced ST depression,, are not ACS, but a marker of chronic CAD.) I used to tell my fellows, a patient with hidden CAD, who develops fever for whatever reason, is acutually doing a tread mill test equivalent , and showing off the diagnosis. It is near- foolishness, if we rush them to cath lab.

How can biomarkers help us grade these ACSs?

The high sensitivity troponins not only help us to diagnose NSTEMI, it also tells us which one of them may be innocuous ACS or benign ? Strangely, we are also taught , “No ACS should be considered benign, until you see the coronary anatomy”. I wish patients realise, how difficult it is to practice cardiology, for that matter any field of emergency medicine. You can’t err at the same time , you are not supposed to treat inappropriate as well.

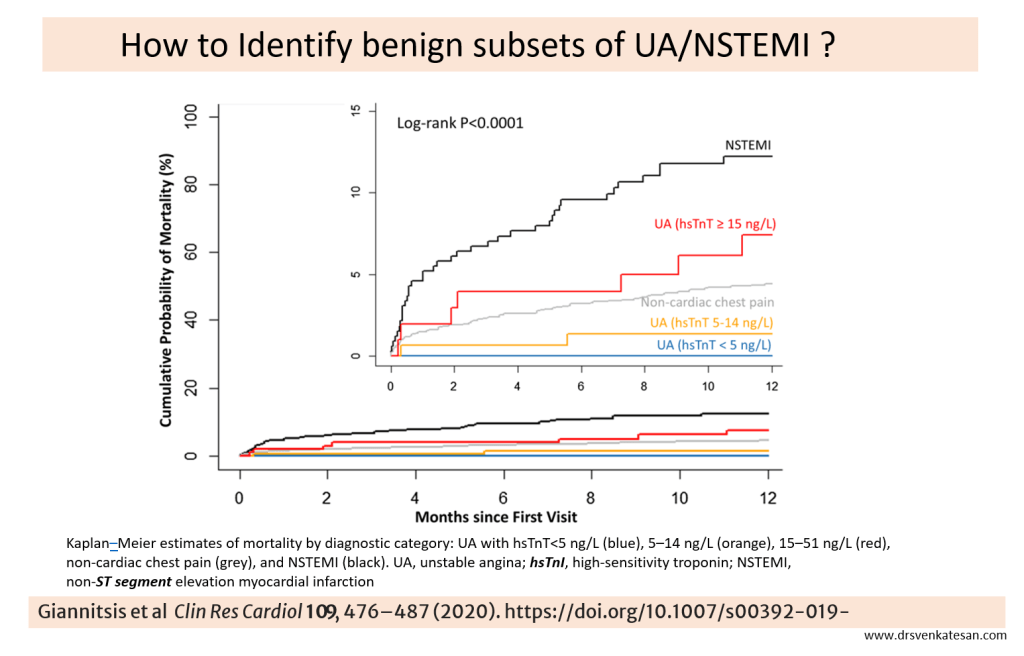

High sensitivity Troponin (hsTnT) do play a useful role in identifying low risk UA/NSTEMI , as seen in the following study. See how the Kaplans diverge dramatically depending upon the hsTnT levels. I don’t understand how the curve of non-cardiac chest pain trespasses in the middle of a Troponin race (False positives? Real concern then)

Final message

Clinical, biochemical, and overall risk profile assessments do help us risk stratify ACS. We have numerous predicting algorithms and scoring systems in UA/NSTEM led by GRACE, etc. Still, it can be a tricky game to make a call on ACS. Mind you, even a coronary angiogram will not bail you out in terms of decision-making and risk prediction. An incidental 80-90% lesion with a normal FFR is quite common.

Avoiding innocuous ACS patients getting admitted in CCUs is a real problem. Of course, getting trapped in a CCU for a few days is better than tampering with the coronaries in the cath lab. Some of the stakeholders may welcome both, but that is not science.

I recall some old guidelines saying not all UA need to be admitted. Many low-risk categories can be managed as outpatients; it is still true. I am not sure how many of us have the courage to do it. Courage alone is not sufficient; the fear of statistical misbehavior of ACS, compounded by potential ridicule from peers or even patients, always haunts.

Reference