Cardio-renal syndrome (CRS) , in reality seems to be , a vague clinical entity, defined and classified into 5 types essentially for our convenience and simplicity. This classification do not contribute to any pathophysiological insights . The fact of the matter is, every patient with heart failure (both acute and chronic) has some amount of renal compromise & vice versa. The link between LV failure and renal compromise is more discussed and documented in the literature than the influence of the right ventricle.

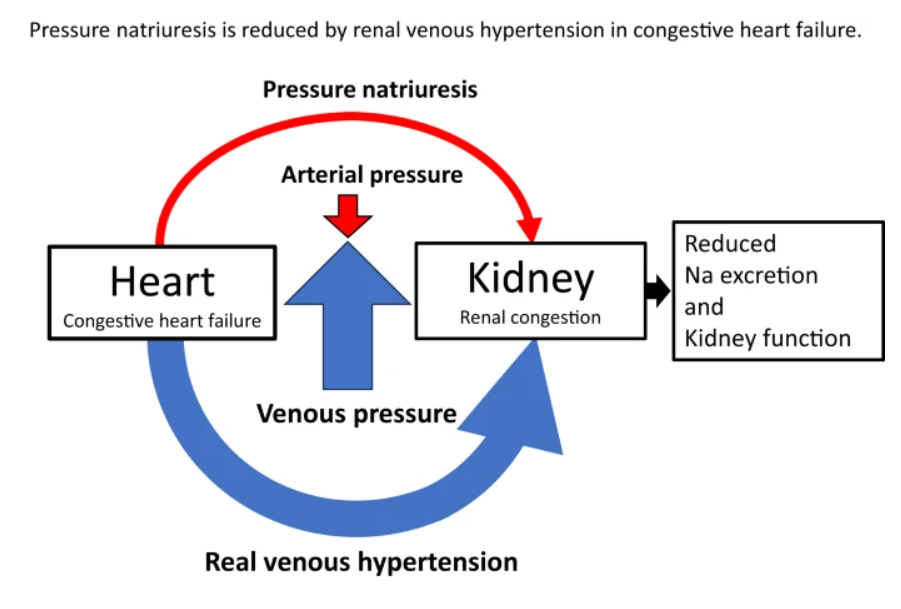

Now evidence is emerging, like hepatic congestion , renal venous congestion also play an important role in compromising renal function. Traditionally, we aim to increase the GFR, by improving renal blood flow, but the real problem may lie in clearing the exit paths of the renal venous system.

A mini review on the topic

Right ventricular (RV) dysfunction in chronic heart failure (HF) contributes to renal dysfunction beyond reduced forward cardiac output, primarily through backward venous congestion elevating inferior vena cava (IVC) pressure and renal venous hypertension. This congestion transmits high central venous pressure (CVP) to renal veins, increasing interstitial pressure, compressing tubules, and impairing glomerular filtration rate (GFR) independent of arterial underperfusion. Studies confirm IVC dilatation and CVP >8 mmHg correlate with worsened renal function, reversible by decongestion.

Venous Congestion Mechanisms

Elevated RV filling pressures cause systemic congestion, reducing trans-renal perfusion pressure (mean arterial pressure minus CVP) and promoting renal parenchymal hypoxia. Animal models show renal venous pressure elevation decreases urine output and GFR more than equivalent arterial hypotension, via tubulo-glomerular feedback disruption and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation. Human data from acute decompensated HF link high RAP/CVP to serum creatinine rise, with decongestion improving GFR in RV failure.

Reflex and Neurohormonal Pathways

RV-driven congestion activates intrarenal mechanoreceptors, triggering sympathetic vasoconstriction and hepatorenal/splenorenal reflexes that exacerbate sodium retention. Splanchnic pooling limits venous capacitance, amplifying intra-abdominal pressure and gut-derived inflammation (e.g., LPS translocation), fostering a proinflammatory milieu worsening cardiorenal interactions. Ventricular interdependence from RV dilation further impairs left ventricular output, compounding renal hypoperfusion.

Clinical Evidence from AHA Context

The AHA Scientific Statement on Cardiorenal Syndrome emphasizes venous hypertension over hypoperfusion in CRS type1 and 2 stressing the importance of ESCAPE/DOSE trial results on diuretic-guided decongestion.

Clinical Implication

Major implication is the role of optimizing diuretic dose in HF, which can reduce renal venous congestion . Treatment strategies aiming to improve pulmonary hypertension and RV function seems important as well.

Final message

If we need to manage cardio-renal syndrome effectively, we need to pull both Cardiologists and Nephrologists to sit in a combined consultation (a difficult proposition in current times), and review patient data, optimizing the strengths and weaknesses of all pillars of heart failure drugs, and (more importantly) fine-tuning the important fifth pillar, the diuretics*.

*For some reason, the literature and cardiology community refuses to admit a blatant truth : Diuretics are life-saving in heart failure.

Further reading

How to treat Congestive Cardio-Renal failure ?