Link to a related post , that might add some sense to the above quote

Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ Category

Forbidden medical quotes : Perils of patient & family empowerment

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged acc aha, best medcial quotes on ethcis, esc, medical ethics, medical guidelines, patient empowerment on March 9, 2026|

Many second opinions might be wrong too … consume it with caution !

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged appropriate procedure, bio ethics, bmj, british journalmof medcial ethcis, clinical decision making, dr s venkatesan, esc, inappropriate interventions, lancet, madras medical college, medcial decsion making, medcial errors, medcial ethics, medical education, medical incompetence, nejm, pateint empowerment, principles of practice of medicine, private vs public health, second opinion, third opionion, venkatesan sangareddi, what ails modern medicine on March 8, 2026|

Getting a second opinion from another expert is a valuable option for our patients when they face a complex decision-making process, especially when a cardiac intervention is advised. No doubt, it is their fundamental rights too.But this could be hard, if the second opinion is sought regarding indication for coronary or interventional procedure.

It is much, much comfortable to concur with the original decision if it is pro -Intervention. (even if it is against your conscience). Vetoing a procedure which was advised by some big hospitals is almost impossible for cardiologists sitting at their office, however experienced they may be. This is because it is sort of going against, the mainstream and defying science as well. Both doctors and physicians are stuck.

I confront such situations often from patients following elite cardiology consults. I had been forthright and genuine and said a firm no or yes to many such procedures . I understood much later, that only a minority of the patients followed my No advice , while invariably they accepted my yes.

After much confabulations , recently, I have made some recalibarations on my values, (decent term for compromise ) despite all the ethical stuff I write in these columns. But, three things I ensure , before giving my opinion which goes against my assessment.

“This procedure is not indicated in the true scientific and moral sense, but 1.If you lack full trust, or 2. If you are not ready to accept the risks of not doing it, or 3. If the fear (of not doing it ), would nag you constantly, then get it done as per the advice of the big guys”.

Final message

Very soon, getting a second* or even third opinion may not really matter as long as doctors are silently captured by the big scientific syndicates. Until we acquire the expertise and courage to identify and ignore the science that is running amok, we certainly fall under the tag of medically incompetent.

*Caution and clarification

Second clinical opinion for helping to arrive at a medical diagnosis is of immense value and a great thing to do. In fact, doctors themselves ask for it when they are in doubt. This article is about second opinion regarding the appropriateness of various interventional procedures that is defining modern medicine.

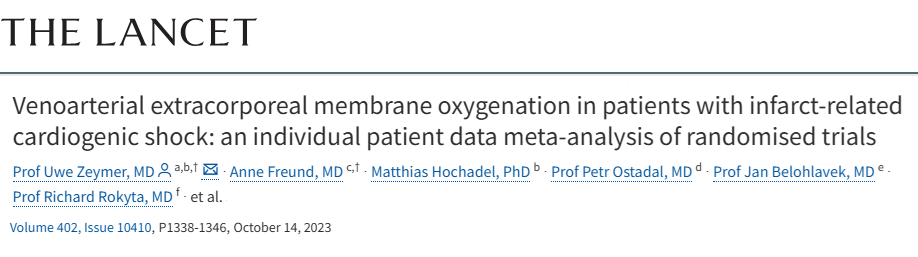

How many lives are saved by ECMO in refractory cardiogenic shock ?

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged ecmo on March 3, 2026|

How many lives are saved by ECMO in refractory cardiogenic shock following STEMI ?

A. Substantial

B. Many

C. Atleaset few

D. None

E. It may even Increase the fatality

Answer

While the popular answer swings between A to D , depending upon the level of optimism & belief system of cardiologists.

However, the correct answer is likely to be D(Ref 1) .

*While C, is quiet possible, E is very much a reality all experienced cardiologist would know.

Postamble

* My non-academic opinion is, ECMO and other MCS devices, are primarily, “guilt-relieving or professional pride delivering” toolkits for the patient’s family and cardiologists, respectively.

Reference

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(23)01607-0/abstract

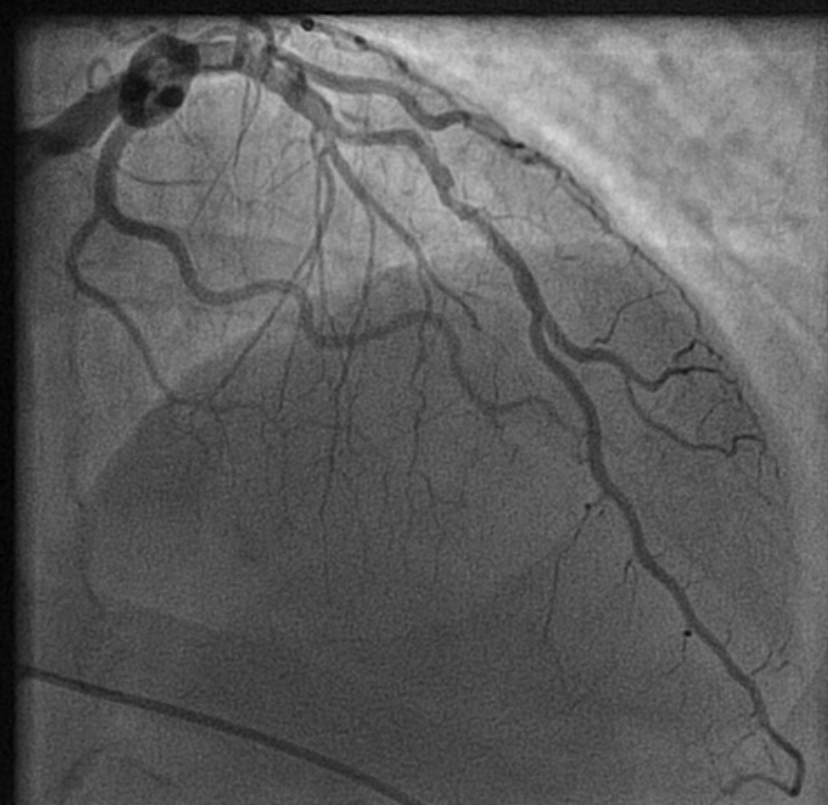

Does CABGs really prevent future MIs and deaths ?

Posted in Uncategorized on March 2, 2026|

This is a very crucial question debated, by cardiologists , cardiac surgeons for long decades (of course our patients too need an answer desperately)

Will CABG prevent or reduce future MI risk ?

The answer is not at all simple , most of us are still tentative.

Have a look at the conclusion of these two famous studies. STICH and STICHES. Hope, we could reach closer to a clear answer.Ofcourse, the study population may not fit in to all the CAD population we come across. Still, it conveys some useful information about this issue.

Final mesage

It is indeed true a STICH in time , really saves nine.

Postamble

The toughness of answering this question lies in the fact, it takes hardly three minutes , for a non flow limiting 30% lesion to transform to a life threatening ACS.

Real world data reveals, most patients with multivessel CAD harbor, a minimum of half a dozen non flow limiting lesions. CABG has a huge edge, in this situation ,as most of these lesions are proximal to bypass conduit.

Counter point

Lastly , and most importantly, it is the intensive medical management and life style modifications, that will determine, whether CABGs are going to work, as it did , to the lucky patients of STICHES cohort.

Journal club : Pregnancy as a cardio vascular stress test

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged gdm and oih in pregnancy, jam study on pregnancy, preganancy and cad risk, pregancy and heart disease on February 19, 2026|

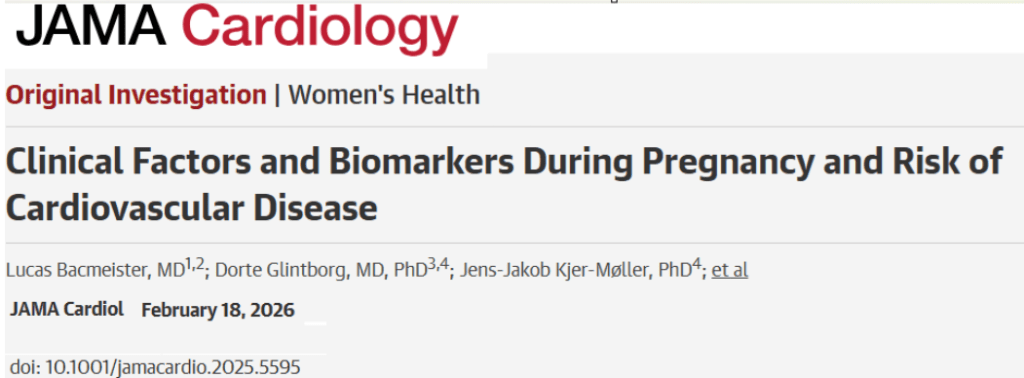

The study in recent issue of JAMA Cardiology examines clinical factors and biomarkers (likely NT-proBNP, troponins, SfLT, lipids) measured during pregnancy to predict long-term maternal cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, positioning pregnancy as a “stress test” window. Its strengths include a large cohort, long-term follow-up, and subgroup consistency, offering actionable early risk stratification to guide preventive interventions and improve outcomes in women

Design Flaws

This cohort analysis reports CVD prediction over a median follow-up ( 10+ years). The major problem with this study is , it has omitted several key confounders that could bias long-term CVD predictions from pregnancy biomarkers, including pre-pregnancy BMI/obesity, smoking status, family history of CVD, socioeconomic status, psychosocial stress/depression, air pollution exposure (e.g., PM2.5), genetic/epigenetic factors (e.g., polygenic risk scores), These time-varying elements, unadjusted in Cox models, likely inflate biomarker associations over the long follow-up period .

Boxplots show the distribution of biomarker concentrations, stratified by the occurrence of CVD during follow-up at gestational up to 29 weeks. hs-cTnI indicates high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; PlGF, placental growth factor; sFlt-1, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Final message

It is well known that pregnancies complicated by HT and GDM may add future risk for CVD. Using pregnancy as a universal cardiovascular stress test may appear good on paper …but it can’t be purely biochemical prediction. It should be primarily clinical follow-up and accounting for other influential risk factors. This study is too much extrapolated and biochemistry focused. Suggesting a costly biochemical panel to predict CVD risk in a huge population of pregnant women appears a futile extravaganza.

Reference

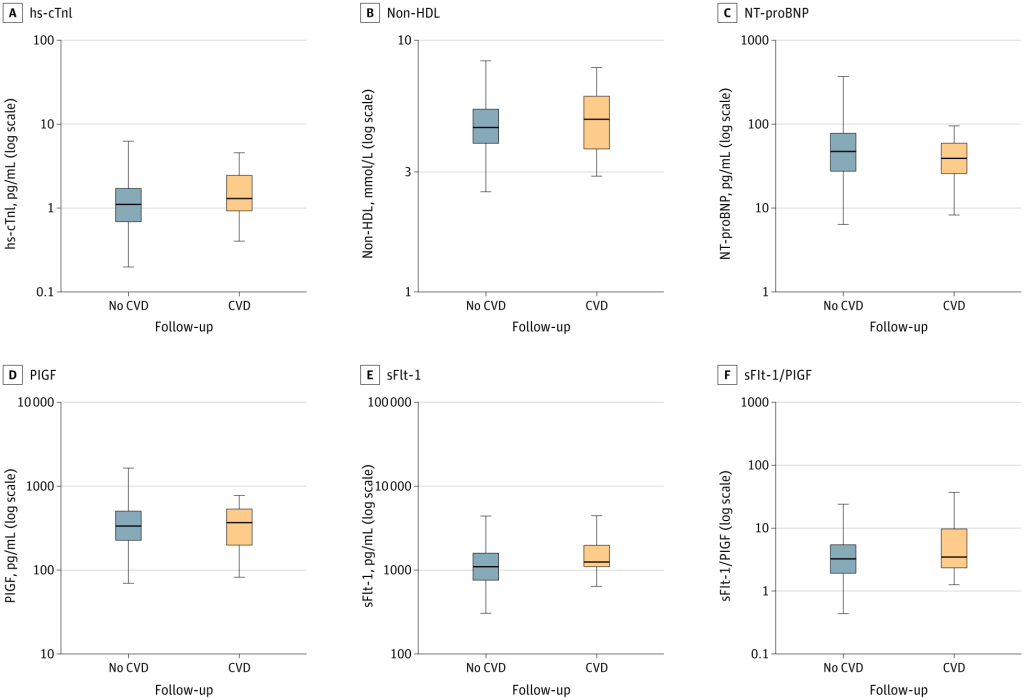

Journal Impact factors(IF) : Nothing to do with manuscript credibility & worthiness !

Posted in Uncategorized on February 17, 2026|

The perceived superiority of journal impact factors (IF) creates a false hierarchy in academia, often equating high IF with superior research quality despite its flaws. Now true scientists are thinking how to counter this hype by advocating for assessments based on actual content and contributions, marking a vital shift toward fairer evaluations.

Pseudo-Superiority of IF

IF confuses journal prestige with individual article merit, as a few highly cited papers skew averages while most receive minimal attention . It fosters misuse in promotions and funding, and invites manipulation like self-citations or favoring reviews . Most importantly, ignores experince and locally published science . The current research assessment models falsifies innovation, ethically burdens top journals, and penalizes genuine works that lacks immediate citations .

DORA’s Welcome Role

DORA explicitly urges eliminating IF reliance for evaluations, prioritizing scientific content, diverse outputs (e.g., datasets), and qualitative metrics With over 2,500 signatories, it drives cultural change in academia, including medicine, by promoting article-level assessments and reducing IF hype .This movement fosters equitable progress, allowing evidence-based research to thrive beyond journal names .

Final message

In this AI era , very often IF also makes an artifitical Impact in academia. Believing IF, as an index of greatness of a research paper … can be a sign of scientific illiteracy. Let us become a member of DORA and try to catch up with the pathways to truth.

Reference

1.Ali MJ. Impact factor under attack! Are the criticisms justified? Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021 Apr;69(4):790. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_281_21. PMID: 33727435; PMCID: PMC8012931.

2.The allure of the journal impact factor holds firm, despite its flaws https://www.nature.com/nature-index/news/allure-journal-impact-factor-holds-firm-despite-flaws

3.Is it Time to Abandon the Impact Factor? https://gmdpacademy.org/news/is-it-time-to-abandon-the-impact-factor/

New age Lipidology : The untold story of bad HDL & good LDL !

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged apo A1 A2, apo b 100, apo b vs apo a, apo b vs ldl ratio, apo protien little a, apolipoprotein, bad hdl and good ldl, dyslipidemia, good ldl and bad ldl, hdl dysfunction, hyperlipidemia, is hdl really good ?, ldl dysfunction, misnomers in hyperlipdemia on February 10, 2026|

From kindergarten, we cherish stories. After adolescence, we dive into fiction. Then in college , science becomes sacred , and we believe, it is an eternal truth.

What a naive notion ? Science mirrors fiction and evolves relentlessly. Yesterday’s facts, become today’s fallacies with the stroke of a keyboard.

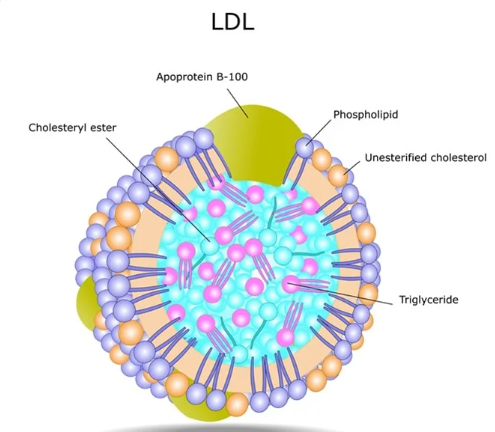

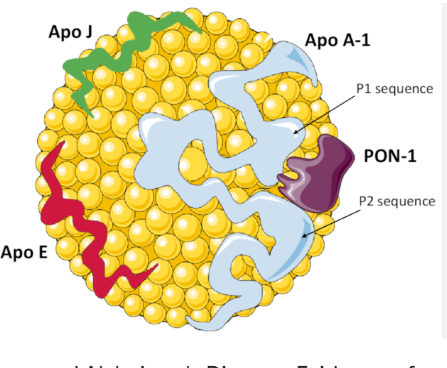

The myth of HDL as “good cholesterol” has been continuously propagated to the public and is etched in our (Patients & Physicians) minds. Likewise, LDL’s portrayal as the ultimate villain persists. Yet, emerging evidence flip-flops this narrative. Large, buoyant LDL particles appear harmless, even protective, while dysfunctional HDL may harbor hidden dangers.

This ignorance-based lipidology stems from oversimplified dogma, that ignores particle size, protien content, and its function. Large, fluffy LDL evades arterial infiltration, unlike small, dense variants. Meanwhile , dysfunctional HDL, oxidized or inflamed, loses its anti-atherogenic prowess and may promote oxidation and inflammation. (This may look like an exaggerated statement, but the fact that the largest popualtion at CAD risk : south asian metabolic syndrome, have a normal LDL level , tells us a chilling truth and mis- understanding about the lipid mediated CVD.

The curious paradox in dyslipdemia : It is the protien fraction that dictates the risk & benefit

In dyslipidemia, a key paradox exists. The protein fraction apolipoprotein that determine true risk and benefit, not lipid content alone.

ApoB-100

Apo B100 forms the structural backbone of atherogenic LDL. There is one Apo B 100 particles one molecule of LDL. It quantifies total harmful burden.Unlike LDL-C (which measures cholesterol load), ApoB-100 directly tallies particle count for superior CVD risk prediction. In large buoyant LDL, reduced ApoB-100 atherogenicity makes these particles largely benign and non-infiltrative.

ApoA-I/ApoA-II in HDL

ApoA-I (70% HDL protein) activates LCAT for cholesterol esterification and drives ABCA1-mediated efflux from macrophages.

It also suppresses LDL oxidation and vascular inflammation, embodying HDL’s core anti-atherogenic shield.

HDL structure

ApoA-II stabilizes HDL size/composition but impairs ApoA-I function in dysfunctional states converint HDLto a pro-inflammatory molecule. ApoB/ApoA-I ratio is key for the proper functioning of HDL. It is also proven, that the beneficial effect of HDL is lost beyond 60mg/dl.

Final message

Whenever we discuss hyperlipidemia, we falsely blame the lipids for endothelial injury .Realistically ,it is the protein sub-fragment Apo B 100 , which acts like a knife and hides within the lipid core , and attack the intact endothelium. There is no empty or toothless LDL molecule without Apo-B. However, there is a well known phenomenon of large bloated LDL , with excess foamy cholesterol,that sort of covers sharp edges of the Apo-B* like an umbrella and reduce the risk of endothelial injury.

*No reference : A pure logical Imagination.

Next query in queue : Are we sure , the statins,Rapathas & Inclisarans always reduce only the bad LDL ? (or it may reduce good LDL as well and give us a pseudo sense of bliss)

Find your own answer

Reference

Overlap between Warfarin embryopathy and fetopathy

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged 5mg warfarin risk of embryopathy, acitrom fetopathy, dose of warfarin and embryopathy risk, early vs late warfarin embryopathy, embryo vs fetus cut off time, embryo vs fetus defintion, fetal cartilage growth, heparin bridge in pregancny, mechansim of warfarin embryopathy, oac in pregancy, prosthetic valve in preganancy oac warfarin management, warfarin embryopathy vs wararin fetopathy, warfarin vs acitrom on February 9, 2026|

Before going into the topic, let us make it clear what is the real cut-off point between an embryo and fetus. All standard literature indicates an embryo becomes a fetus at the beginning of the 9th week when organogenesis, is to a large extent, completed. Ultrasonically, Crown-rump length > 35, beyond Carnegie stage 23, etc are used . But, practically, I think we have extended it up to 12 weeks, i.e., the first trimester. By this time, the fetus assumes a human shape in all aspects, moves the limbs, head, spine erect, eyes open, etc. Getting deep into this, the time-based cut-off definition is obviously not ideal. The errors of counting from the day of conception vs LMP is a big confounder in the published literature.

This may appear an non- issue , for most obsterticians , but specifcally in warfarin related embryoapthy , timing is everything*. Warfarin targets late embryo-to early fetal phase. (6-12weeks) This issue becomes very practical, when a pregannt women on prosthetic valve with warfarin reports to an obstercian at 10 weeks . Will he/she take a risk of preventing final phase of fetal warfarin related injury vs Heparin switch related prosthetic valve obstruction? (Ofcourse the Heparin bridge seems to have collapsed in most high risk thrombotic clinical settings. )

*Realise for fetopathy, there is no timing issue .It affects entire pregancy after 8 weeks.

Mechanism of Warfarin Embryo-fetopathy

Warfarin inhibits vitamin K epoxide reductase blocking gamma-carboxylation of proteins like osteocalcin and matrix protein, leading to skeletal defects in the classic embryopathy window (weeks 6-12). This is a biochemical not genetic or mutational defect . In the fetus, the side effects are due to its intended action, ie exccessive bleeding.

| Warfarin Embryopathy | Warfarin Fetopathy | |

|---|---|---|

| Timing of Exposure | Primarily first trimester (typically 6-12) 6-10% risk with first-trimester exposure | Second and third trimesters (after week 12) The exact incidence of fetopathy not known.it can be up to 25 % if we include all spectrum from minor CNS defects to still births. (Surprising there is a need for more data capture in this ) |

| Mechanism | Primarily bio-chemical : Affects cartilage and bone formation via inhibition of vitamin K-dependent proteins like osteocalcin | Related to anticoagulation effects leading to hemorrhage, as well as CNS and developmental disruptions in the growing fetus |

| Clinical Features | Nasal hypoplasia Stippled epiphyses (calcified spots on bones visible on X-ray) – Skeletal abnormalities (e.g., short limbs, brachydactyly) – Facial dysmorphism – | CNS abnormalities (microcephaly, hydrocephalus, Dandy-Walker malformation) Eye anomalies (e.g., optic atrophy, microphthalmia) Intracranial or fetal hemorrhage Fetal loss, Neonatal bleeding |

| Overall Risk and Outcomes | Structural birth defects .Not dose-dependent beyond a certain threshold | Hemorrhagic and growth-related complications; more dose-dependent, with lower risks at low doses < 5mg |

Is there a overlap betweeen embryopathy and fetopathy ?

Obviously yes. If exposure occurs around weeks 9-12 (early fetal stage), it could contribute to both structural anomalies (embryopathy-like) and hemorrhagic risks (fetopathy-like). Continuous or exposure across trimesters results in a combined phenotype, sometimes referred to as “fetal warfarin syndrome” (FWS), with mixed skeletal and CNS defects

Warfarin risk profile with reference to time : Is first first 6 weeks warfarin absolutely safe ?

It seems so. There is no evidence for any defects in preganct women taking htis in the first 6 week. It is a paradox like because almost 3/4 th of embryonal period , warfarin exposure is safe. Tihs satement is can be perplexing , as trnstion perios of embti to fetus is stull not clear and it is ot uniform in all . It aslo assumes embrys dont have cartialge so vitamin k is safe

Warfrin dose : Low vs high dose risk ?

Dose plays a role too: Low-dose warfarin (≤5 mg/day) reduces fetopathy risk but doesn’t eliminate embryopathy risk. The overall incidence of FWS (combining both) is estimated at 4-8% with warfarin use in pregnancy, with higher risks if exposure spans multiple periods. The much-celebrated 5 mg warfarin cutoff for safety, adopted by most advisory committees, requires a relook.

Warfarin effect on cardiac develoment ?

Wrafarin is well recognised to cause VSD, PDA , but rarely cono truncal anomaly.This explains the warfarin doesnt interupt early cardaic development and looping that stastrs at 4 weeks. The final septal sealing which happens in 8 the week is affected.

Warfarin vs Acitrom comparison (Barcellona D et alWarfarin or acenocoumarol: which is better in the management of oral anticoagulants? Thromb Haemost. 1998)

Acitrom is almost doubly powerful. 2.5mg of Acitrom is equal to 5 mg of warfarin. Acitrom has a half-life of approximately 10 hours. Because of this shorter duration in the body, stopping the medication and administering Vitamin K allows for a quicker reversal of the bleeding risk compared to longer-acting agent like warfarin.

A comparative chart is available here Source :https://doi.org/10.18203/2349-3933.ijam20240367

Final mesage

1.Though we have strictly defined the time line between embryo and fetus (end of 8weeks) we are not clear when exactly the embryo, begins to synthesize cartilage and try to become a fetus.

2.The side effects of warfarin are purely bio-chemical and not due to genetic interruption or mutations.

3.To be more precise, the embryo is affected during it’s late phase, not in the first 6 weeks.

4.Low dose Warfarin is safe for the fetus, but not for the embryo. (The popular 5mg safety net is for optimising the risk, not for elimination)

Reference

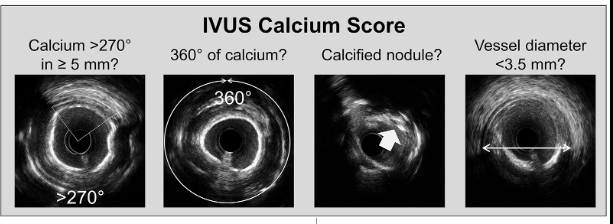

Intra coronary calcium : Are they really thrombogenic ?

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged calcific nodule, calcium phosphate crustals, clooting factors, endothelial coverge of calcific nodule, eruptive calcific noduale, free Ionic calcium vs calcium crystals, is calcium thrombogenic?, ivl for calcium, ivl wolverine angiosculpt, opn balloon, rotoblator, thrombsosis risk in mitral valve or aortic valve calcium on February 6, 2026|

Intra coronary calcium : Are they really pro-thrombogenic ?

A.Yes

B. No ,

C. Yes & No ,

D.Don’t know ?

If you had answered either A or D , you may read further.

Calcium in the coronary artery is usually in the intimal/medial plane. It is covered by fibrous caps of varying thickness or just a single endothelial layer. Thus, calcium is not exposed to blood directly. Even if it is exposed, as in an eruptive nodule, the formation of thrombus is not attributed to calcium per se but to the exposure of subendothelial tissue factors .

1.If calcium is directly exposed to blood, does it trigger a clot?

Yes is the answer from most of us and even from pathologists. But the proof is vague. If that is the case, every degenerative, calcific aortic or mitral valves must form recurrent thrombosis. Thrombosis over these calcification are very rare , with 7500 liters blood traverse over it every day. (Now you know, why your answer was wrong)

2.Is it not true, calcium is essential in the clot forming process ?

Yes, Calcium is essential for the blood coagulation process. It is required for several key steps in both the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways, acting as a cofactor for the activation of various clotting factors.

Please mind, this free calcium is totally different . They are ionized calcium circulating in the blood , always charged to bind with a clotting factor.

3.Then how calcium is not pro thrombotic ?

Read below

4. Is the calcium in the blood and deposited Calcium Different?

Absolutely. The calcium that takes part in the coagulation process is free ionic calcium. Deposited calcium, within arterial plaques, valvular calcifications, is fundamentally different. It exists primarily as insoluble crystalline compounds, such as hydroxyapatite (a form of calcium phosphate) which is the same mineral found in bone. This is a solid, bound form resulting from dystrophic or metastatic calcification process. The are largely Bio -Inert atleast with reference to coagulation.

Final message :

Coronary calcium, whether within the tissue plane or exposed to the lumen, is not directly thrombogenic. They are dead-end inert products of atherosclerosis. However, the prothrombotic trigger occurs with some of the sharp calcium crystals or nodules when they injure the endothelium and expose the subendothelial tissue factors. Abluminal endothelial injury from the intimal calcium is far less common* in most chronic CAD, unless , some aggressive humans decide to wage a intra-coronary calcium warfare, to facilitate stent deployment .

*Disproportionate calcium loading in the shoulder region of the plaque can make a plaque vulnerable. Having said that, overall in a holistic atherosclerotic landscape, calcium is more of an enemy of cardiologists, who face a hurdle to place stents than the patient who harbor it..